Imperial Exam

Imperial Examination System (科举)

The Chinese Imperial Examination System focused on testing a student’s knowledge of poetic style and phonetics, for an original poem could clearly demonstrate one’s mastery of the rules that sustained the Chinese Imperial Knowledge System.

Qing Dynasty examination hall in Beijing, 1899.

Poetic Structure

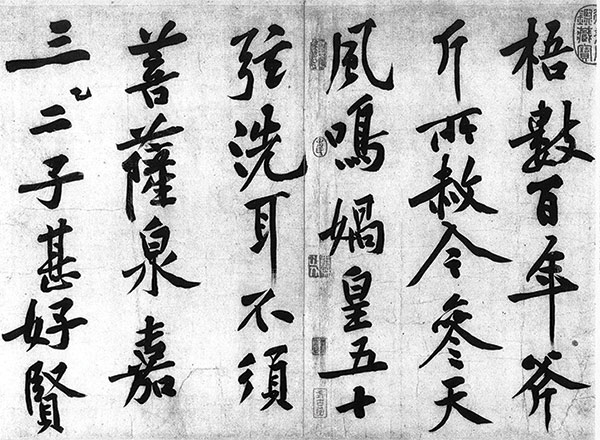

Poem of Sōng Fēng Gé (松風閣詩) by Huang Tingjian (黃庭堅) (running script).

A good poem needed to balance the elements of yin-yang through regulated tonal patterns like those found in the rime tables, to balance the meaning of words by using parallel structure between lines, and to allude to important moral codes, historical scenes, and aesthetic practices. Unlike a pledge of allegiance or other contracts, a successful poem revealed not only the candidate’s allegiance to the Empire, but also revealed that a person had become fully acculturated, with internalized norms naturally flowing through them as an extension of their own identity.

What If?

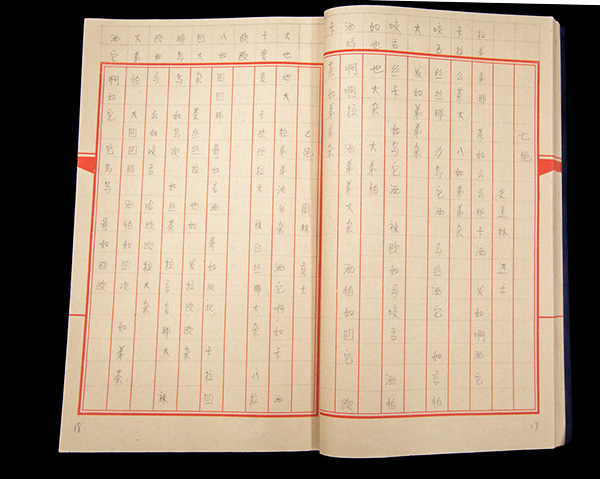

If English had been the medium of the Imperial Examination, students would have needed to compose poetry to demonstrate their mastery of the Imperial Knowledge System. For over 1,000 years, these poetic forms were adopted in Sino-Korean, Sino-Vietnamese, and Sino-Japanese. In 1997, Professor Stalling invented the Sino-English Classical Chinese genre by limiting English to a vocabulary of 3,000 monosyllable words constrained by the rules of Classical Chinese poetry. This helps English speakers understand how to regulate language in the ways valued by classical Chinese poetics, through direct, hands-on experience.

English jueju transcribed into Pinying.